Irish pavilion unveils in search of hy-brasil at biennale

A team of five architects unveils In Search of Hy-Brasil at the Irish Pavilion for the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, which runs from May 20 to November 26, 2023. The temporary exhibition examines remote island communities, their culture and mythology, in order to inspire new ways of inhabiting the world. designboom sat down with Peter Cody, one of the curators of the pavilion, to discuss the Irish contribution to this year’s Architecture Biennale.

‘The project is looking at islands, particularly along Ireland’s western seaboard, and the unique culture that exists there. As we go forward in dealing with issues of climate change, analyzing how people in these communities live, deal with resources, and adjust themselves accordingly to the environment, can be very instructive to teach us how to respond to climate change,’ introduces Peter Cody, co-curator of the Irish Pavilion.

In Search of Hy-Brasil inside at the Irish Pavilion | image © designboom

the peripheral becoming central at the irish pavilion

Responding to Lesley Lokko’s theme, The Laboratory of the Future, the Irish Pavilion‘s In Search of Hy-Brasil presents fieldwork from Ireland’s remote islands. The team of curators; Peter Carroll, Peter Cody, Elizabeth Hatz, Mary Laheen, Joseph Mackey; explored the intrinsic links between Irish language and landscape. The team believes that the modern world has lost their connection, and that we can learn from rural island communities and their relationship with the environment. The name stems from the ancient story of Hy-Brasil, a mythical Atlantic island that embodies the possibility of re-imagining Ireland.

‘We were interested in the island’s people, and how they are viewed as peripheral yet in terms of renewable energy and recycling, the Aran Islands are way ahead of the Irish mainland. They are very cohesive communities that have a lot of agency, and come together to deal with major challenges,’ elaborates Peter Cody, on why the Irish Pavilion focused on remote island cultures.

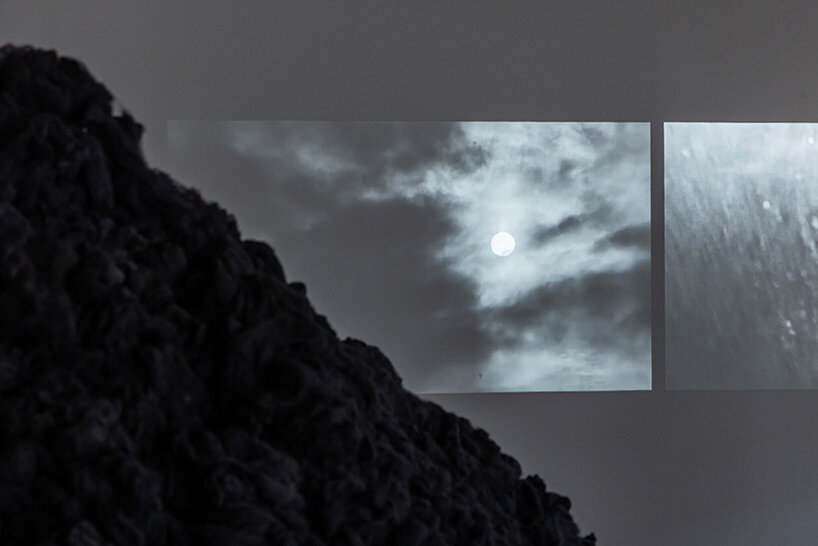

the exhibit examines remote island communities, their culture and mythology | image by Ste Murray

Detailed research of three remote irish islands

In research for the Biennale installation, the curators studied the island landscapes of Inis Meáin (Inishmaan), UNESCO World Heritage site Sceilg Mhicíl (Skellig Michael) and Cliara (Clare Island) through drawing, survey, film, sound, model, mapping, and story. The installation offers an immersive experience that takes Biennale visitors to the depths of Ireland, drawing connections between the remote island’s social fabric, cultural landscape and ecology.

‘We investigated three main islands. Each of them is represented in a different way. Inis Meáin through a film. To illustrate Sceilig Mhichíl we created a wool model, made from Native Galway sheep. For Cliara, we display a complete Biological Survey of over 8500 species of flora and fauna that live there,’ describes Peter Cody on the investigation process.

Irish Pavilion believes that we can learn from rural island communities and their relationship with the environment

image by Ste Murray

Local recycled materials compose the exhibition

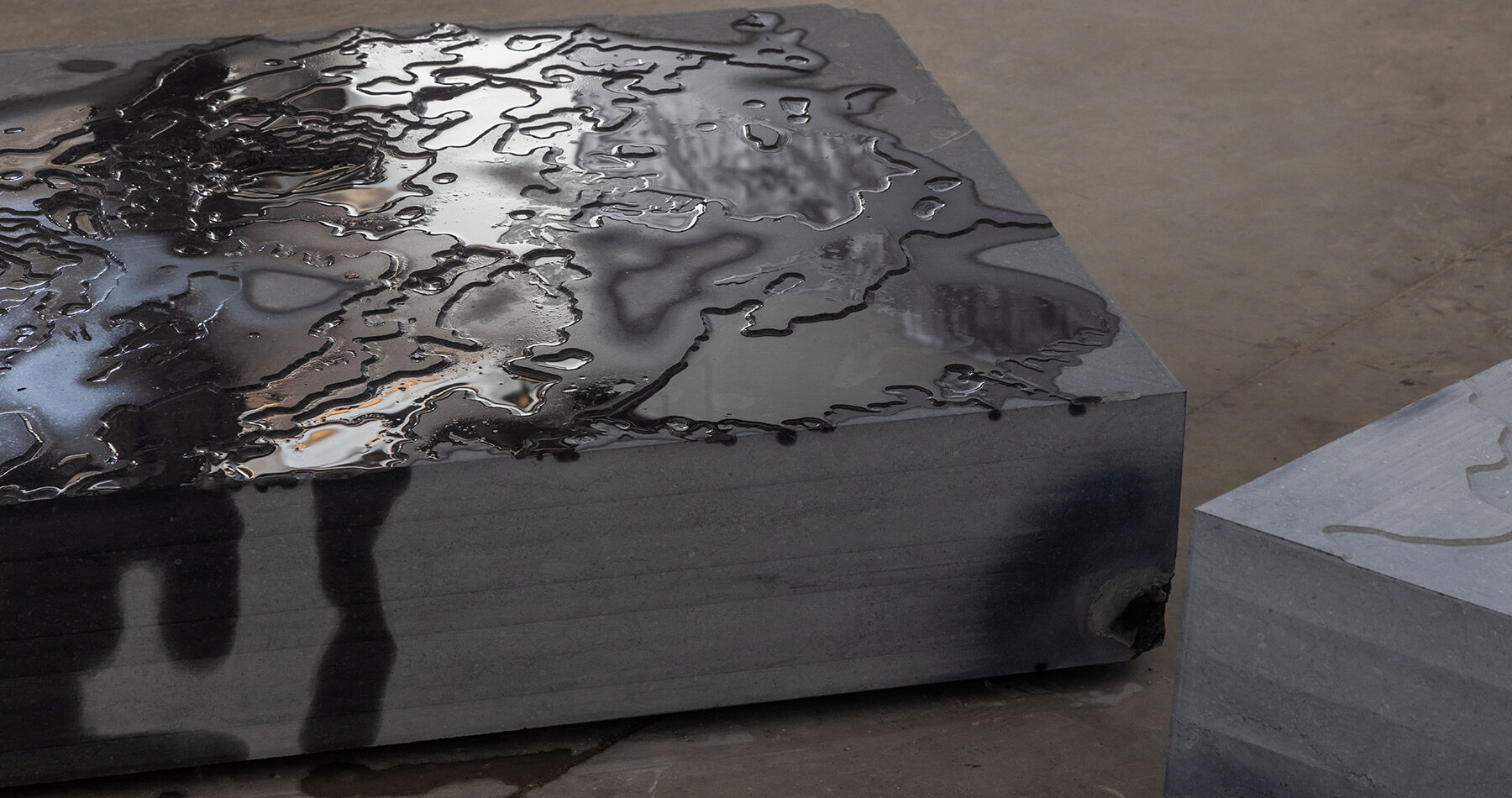

The installation also consists of large limestone slabs showing negative models of the three islands and their related ocean floor. Local materials build hands-on tactile displays that celebrate their use in innovative and unorthodox ways. These include a hung linen tapestry mapping the topography of Ireland’s maritime zone and sea sack seats salvaged from 2000 meters of fishing rope.

‘We are a part of the environment, and it’s important that we understand our place, so that we can care and look after nature. Otherwise, it’s just invisible and we forget about it. People who live in the rural island communities never lost that connection, nature is still in their vocabulary and they are still very aware of it,’ concludes Peter Cody on being aware of our place in nature. (read the interview in full below)

landscape studies were conducted on Inis Meáin, Sceilg Mhicíl and Cliara | image by Ste Murray

Interview with peter cody at Venice architecture biennale

designboom (DB): Briefly explain the the Irish Pavilion’s ‘In Search of Hy-Brasil’ project?

Peter Cody (PC): The project is looking at islands, particularly along Ireland’s western seaboard, and the unique culture that exists there. Here, communities live in a very particular way, which we, on Ireland’s mainland, talk about as being peripheral, but in fact, remote island culture has a huge impact on the country’s cultural footprint.

As we go forward in dealing with issues of climate change, analyzing how people in these communities live, deal with resources, and adjust themselves accordingly to the environment, can be very instructive. So rather than be peripheral, it becomes very central.

how people in these communities live can be very instructive to teach us how to respond to climate change

image by Ste Murray

DB: Why did you choose Ireland’s remote islands as the setting for the exhibition?

PC: There is a lot to be learned from remote island communities, for example they are very careful with their resources. Things are much harder to come by, and because of that they utilize everything. There’s no soil naturally, it is made, so all farming takes such effort and needs to be highly looked after. This is a great learning tool for us, to consider the intensive practices that we have used, and the detriment of those practices on the environment.

Another thing that amplifies the community’s relationship with nature is the Irish language. Irish has a particular way of describing nature that is very different from English. In Irish, there are far more words to describe elements of the landscape, and even to describe how you situate yourself within nature. Irish understands the environment differently, and part of the effect of English being the dominant language was this loss of expression and way of thinking about nature.

In modern times to face the issues of climate change, we have to start listening to the tacit knowledge that is deeply embedded in rural cultures around the world, where this connection with nature has survived. It’s knowledge that we should be thinking about utilizing. The Pavilion argues that there’s no technical solution to climate change, it’s not a legalistic problem, it’s a cultural problem. We aim to evoke a conversation between people to discuss deep structural changes about how we live our lives, and how there are no easy solutions.

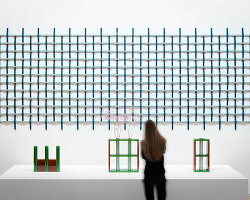

in irish there are far more words to describe elements of the landscape than english | image © designboom

DB: How did you conduct research for this project?

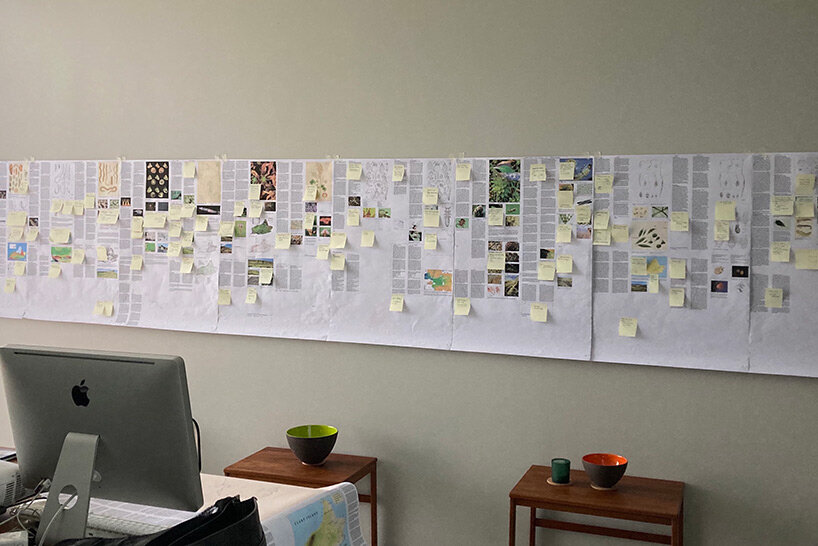

PC: The first thing we did was meet about 50 or 60 people across ten meetings over zoom, with locals from the islands but from different walks of life. There were fishermen, academics, researchers, scientists, writers, so a very diverse body of people, brought together in groups. What I found most interesting was the passion for the subject of environmental issues that they all shared, but approached in different ways. There’s so much synergy but also a lot of complex interweaving strands that make up these places. And then, translating all of those conversations into this room becomes the challenge.

We also utilized a Clare Island study from the Royal Irish Academy, which was done at the beginning of the 20th century by Robert Lloyd Praeger and his colleagues. It was repeated from the 1990s for about 20 years and was completed last year. It’s a complete Biological Survey and at the time was probably the most complete survey of any place on Earth. On Clare Island, there are 8500 species of flora and fauna, all documented, so it is incredible scientific research that we were given access to.

We were interested in the island’s people, and how they are viewed as peripheral yet in terms of renewable energy and recycling, the Aran Islands are way ahead of the Irish mainland. The rural islands are very cohesive communities that have a lot of agency, and come together to deal with major challenges.

rural islands are very cohesive communities that have a lot of agency | image © designboom

DB: Do you think that this deeper connection with ecology that exists in these rural island communities leads to a better quality of life?

PC: You’d hope so. If we want to deal with the issue of climate change, we have to re-establish our connection with the natural world, and understand that we are a part of it. You can’t have technology interface between us and it. For this reason we only use natural light in the exhibition. If it gets dark, it gets dark, when you can’t see, you can’t see, we don’t need to optimize everything at every moment. Sometimes, you have to go with your circadian rhythm and accept the ebb and flow of things to realize that we’re part of this natural system.

One of the amazing things about the Clare Island study, was a microscopic creature, who’s reproductive cycle works in tandem with the tides. In this way, that creature is connected with the planets. We are a part of that system, and it’s really important that we understand our place, so that we can care and look after nature. Otherwise, it’s just invisible and we forgot about it. People who live in the rural island communities never lost that connection, nature is still in their vocabulary and they are still very aware of it.

sea sacks are salvaged from sea rope that were pulled from the ocean | image by Ste Murray

DB: For readers who won’t get to visit the Irish Pavilion at the Biennale, how would you physically describe the installation?

PC: We have several items that are all in conversation with each other but are also in conversation with the room. We investigated three main islands; Sceilig Mhichíl, Inis Meáin, and Clare Island. Each of them is represented in a different way. Inis Meáin through a film, which is made by Red Pepper Productions. To illustrate Sceilig Mhichíl we created a wool model, made from Galway sheep, which is the only native Irish sheep that is still used for wool, textiles or yarn. On top of the black wool displays a clay model of the monastery and hermitage, and on the floor we have seaweed. All of the materials have been recycled or repurposed, and can be utilized again.

On the sides we have sea sacks, salvaged from sea rope, where you can sit. Made from 2000 meters of fishing rope that was pulled out of the ocean and filled with wool. The ocean territory map is printed on linen from Northern Ireland, mapping the jurisdiction we have over the ocean which is about ten times greater than the land area. Peter Carroll and his team used lidar mapping and satellite imagery to put this map together.

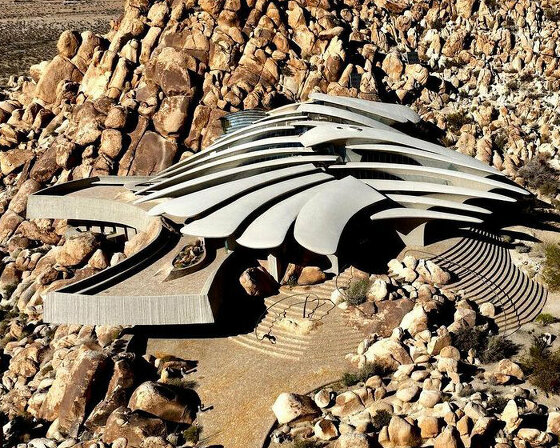

We have large negative limestone models of each island, cut into stone using diamond heads. The inverted models are resemblant to fossils found in sedimentary stone, and are filled with water to create fissures. On the wall, there is a drawing with graphite on tracing paper of Pangaea, demonstrating that at one point, all the continents were just one island. The soundscape was taken from the film but is not synchronized with it, playing local sounds like birds and wind, and, of course, you can always hear the sound of the ocean.

drawing with graphite on tracing paper of pangaea | image by Ste Murray

limestone model of the island inverted | image by Ste Murray

the team of curators, (from left to right, Joseph Mackey, Elizabeth Hatz, Peter Cody, Mary Laheen, Peter Carroll)

project info:

name: In Search of Hy-Brasil

curators: Peter Carroll | Peter Cody | Elizabeth Hatz | Mary Laheen | Joseph Mackey

event: Venice Architecture Biennale 2023

location: Giardini, Venice

Explore designboom’s ongoing coverage of the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale: The Laboratory of the Future here, and follow our dedicated channel on Instagram here.

ARCHITECTURE INTERVIEWS (263)

CLIMATE CHANGE (147)

EXHIBITION DESIGN (527)

VENICE ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE 2023 (40)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.