This year designboom turns 25 years old.

text by Jenny Filipetti

It’s a story we didn’t necessarily think would be told in fractions of a century when we started in 1999. We were the first online magazine in the world, at a time when not everyone even had a computer: before social media, before the internet was a part of most people’s lives, and even then only via slow and expensive dial-up.

Back then, online publishing felt like building a new world– and in fact it required programming and building from scratch a lot of the necessary tools. The internet was mainly text-based, structured around government pages and scientific publications. a magazine needs images: our photos were numerous but small to help ease page loading time.

From the start we wrote from real experience about cultural intents and influences, restraints and contradictions. We stimulated a global discussion, motivated at every turn by the rapport that we established with our readers and the greater design community. ‘Talent is equally distributed, opportunity is not.’ that was the context designboom was founded in, and the guiding light for just about everything we’ve done this past quarter century: a small international team of passionate people, working together initially out of an apartment office in Milan (and then also in an office in Beijing, and in New York). The story of designboom has always been a very human one, and we tried to introduce a certain amount of utopia in most of our projects. Looking back, it’s a story in microcosm about the internet as well: about society, about what our technologies make possible or don’t, about what they nurture or obscure. this article is a little ode to our history through that lens.

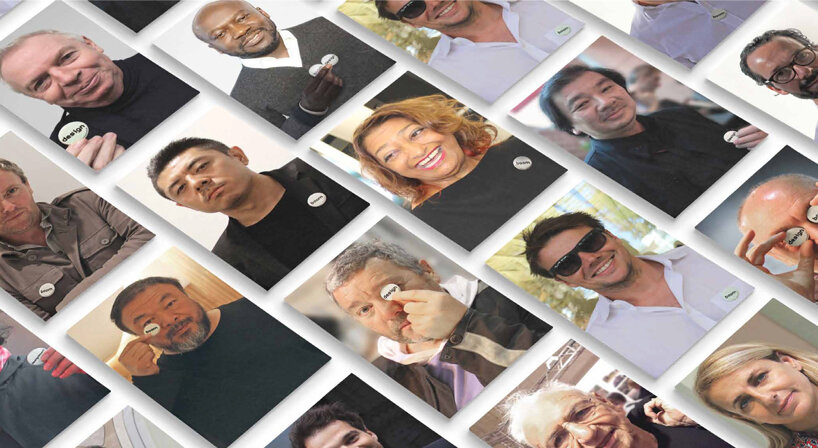

collection of portraits of designers and architects with designboom’s pins

2002: we were a team of six and had been publishing a daily magazine for three years. youtube and facebook didn’t exist yet but recently search engines.

Online publishing remained mostly the realm of the personal (think xanga, livejournal, and geocities). That year we created designboom competitions, developed a web-based system that gave designers from anywhere in the world the chance to submit projects in response to creative open calls, but also retain copyright over anything they shared. After each competition ended, all shortlisted submissions were made publicly available including the date of publication, creating an archive that could be used to defend copyright should a design be utilized without credit or compensation in the future (there were hints already of the possibility that certain companies might exploit creative minds). An international jury of leading design and architecture professionals judged the anonymous submissions for each open call. With Hermès for example we developed a new procedure that saw more than 10,000 people participate.

Birgit and Massimo in the designboom summer office, 2012

education

In 2003, we created ‘design aerobics’, almost undoubtedly the internet’s first online design classes, envisioned as a fitness workout rather than an academic class. For $59 each, up to 100 participants could enrol in 8 annual bimonthly design courses on specific topics, learning about design history and completing weekly exercises reviewed directly by (our editor in chief) Birgit (Lohmann) herself. There were no ‘beginners’ or ‘advanced’ students. Curators, brand managers, and teachers took part alongside lawyers, dentists, and hobbyists.

Out on the rest of the internet, August saw the start of Myspace (the first social media platform to reach a global audience) though it would peak and fade just five years later. WordPress launched in May, and the next few years would usher in the launch of a smattering of design and architecture blogs. The internet still felt like a community, and these early players all knew and read each other’s work. When someone else published something your readers had to see, you published a teaser article with maybe a single photo and a link to the original source where they could ‘read the full story.’

exhibitions

New York design week, 2005: Youtube had just launched; it was still two years before the first iPhone. We invent the designboom mart pop-up, a fair-within-the-fair where we invited emerging designers from all over the world to convene to show off their products and get professional feedback from the buyers and aficionados attending these glittery global events. Exhibition space at the world’s major design fairs is expensive and resource-intensive; recruiting attention once you’re there even more so. The format proved a hit, and over the years we held 40 marts, featuring 30-40 young designers at every one of them: Sydney, Melbourne, Tokyo, Seoul, New York, Toronto, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Saint-Etienne, Valencia. Some of today’s famous names began their journey here, among them Oki Sato (nendo), Joe Gebbia (co-founder of Airbnb), Nicholas Roope, Sam Baron, Nicolas Le Moigne, and Maxim Velcovsky.

We curated material culture exhibitions – ‘rocking chairs’ (results of a competition with Sothebys), ‘handle with care’ 500 contemporary ceramic objects for Designersblock, London, ‘folding chairs’ (competition with 100% Design London), for LA’s annual ‘dwell on design’ events (about ecology and asian design), shows about Korean contemporary art and historic manufacture in Seoul…

in 2007, TIME magazine chose designboom as one of the top 100 design influencers in the world.

Oki Sato (nendo) about the designboom mart

This polyphonic mix of reports, exhibitions, education, and open calls felt entirely natural. We were creating the opportunities we wanted to see in the world. It’s no coincidence that designboom was founded by two experienced industrial designers— not journalists and not corporations—who chose to exclusively hire and work daily alongside a close-knit full-time team of graduates in design, art, or architecture. designboom was a design project to broaden the reach of the creative scene, from the close niches of acclaimed professionals to everybody else with cultural interests. Everything we did was done in-house. Everything we did was personal: redesigning the site every three years to morph alongside our own evolving tastes, sensing where something new was needed and trying to meet it. We went on studio visits, bringing our 3.5 million readers behind the scenes of upcoming and leading designers and architects. We did factory tours of everything from Ferrari cars to Arduino microcontrollers, trying to make visible the processes that shape the products we live among.

It was never easy, then.

It’s not clear if something quite like it could ever happen again, now.

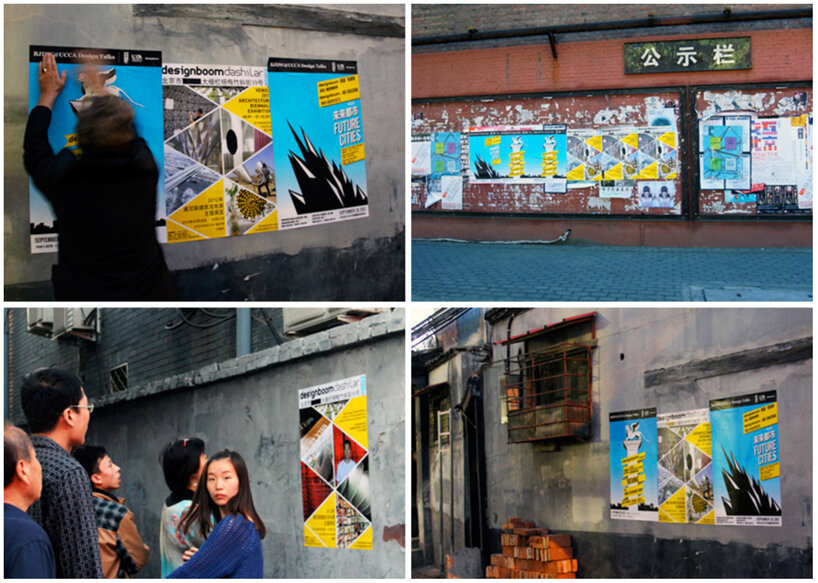

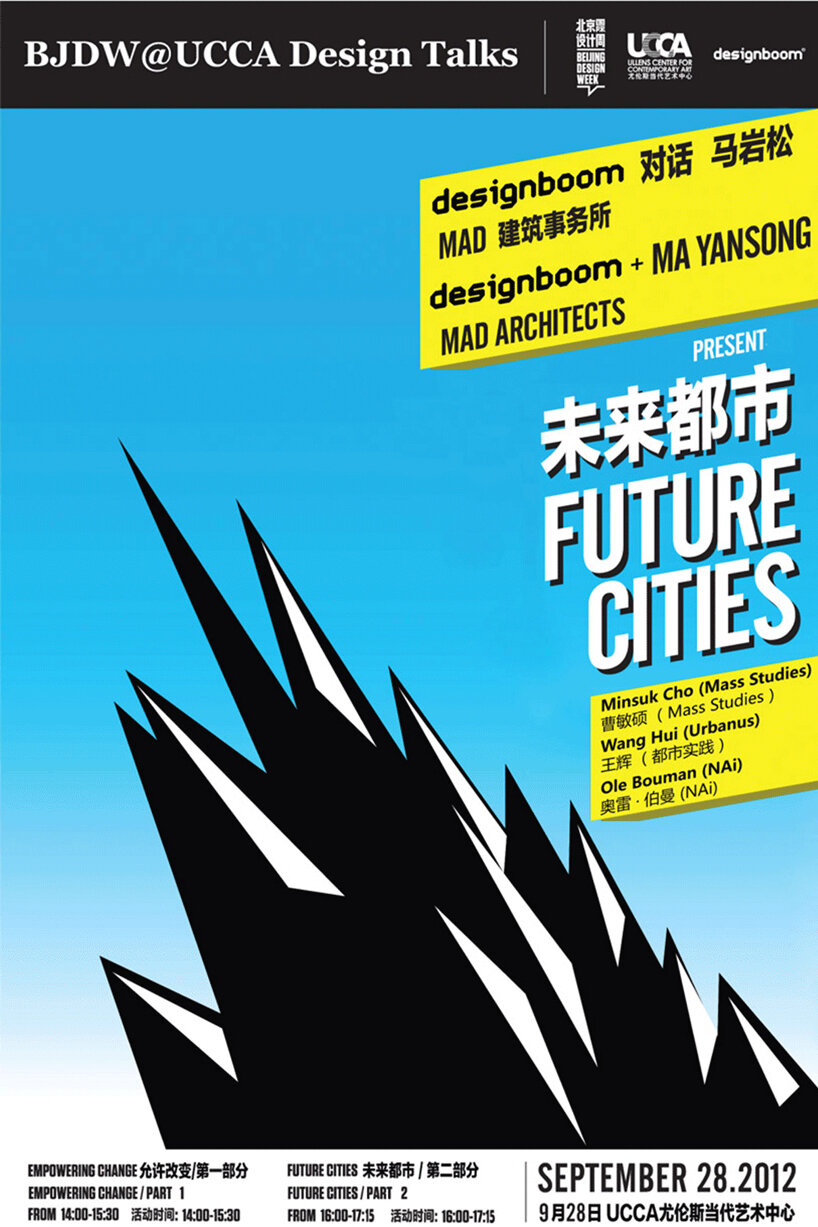

exhibition at designboom’s gallery in Dashilar, a Beijing Hutong, and at UCCA gallery

designboom’s shows in our Dashilar gallery promoted on posters

a horizontal distribution of culture

By the early 2010s almost 2 billion people were online. We opened reader submissions, where anyone from anywhere in the world could share their work directly on designboom in their own voice. Every morning we’d curate and publish the most interesting content. We were proud of these daily articles and saw them as a major contributor to a horizontal distribution of culture, something we had dreamed of since our founding.

By now the internet had experienced its Cambrian explosion of design and architecture publications. Unlike the early days of article teasers and linkbacks, it became common for publications to repost entire article’s worth of photos and information, albeit still providing a ‘hat tip (h/t)’ link at the bottom to show credit. Facebook was a toddler, and Instagram had just been born; at the time both were still mostly about sharing personal snapshots (the latter through its glowy haze of ubiquitous filters). We started to publish in Spanish and Mandarin alongside English. A few years later, in 2014, we created an entire new domain at designboom.cn, published in Mandarin from inside China, free of government oversight or scrutiny thanks to a cultural exchange with their ministry of education.

And yet the rhizomatic, networked version of internet culture was in its twilight.

By then known as the go-to destination for all things architecture, art, and design, designboom rapidly became a sort of press agency for bloggers and journalists. The pace of news consumption accelerated. Hat tips disappeared: people and bots alike began to republish online content fairly instantaneously and in their entirety, without credit. It created flurries of success for some of the designers and architects we featured, but it didn’t build community like the practices of the past had.

Pharell Williams with designboom’s pin

Jenny Holzer with designboom’s pin

Future cities

We continued dreaming and building. From 2012 to 2014 designboom hosted public architecture conferences at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing. Ma Yansong (MAD architects), Wang Hui (URBANUS) and Minsuk Cho (MASS STUDIES) discussed the history of architecture, and its impacts and future developments in China. We opened a gallery in Dashilar, a Beijing Hutong, bringing China’s participation exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale to locals. We launched a series of talks and conversations where Chinese and international design and architecture experts took Dashilar as a case study to investigate how urban planners can both protect an area’s cultural heritage while revitalizing and developing it.

The culture of the internet continued to transform. In the age of smartphones and social media, push notifications and virality reigned supreme, creating new creative tensions and possibilities. It became simultaneously much easier for anyone to create and share content, and much more difficult for them to gather an audience.

Future Cities

Offline, the same evolutionary drives were at work. Our pop-up designboom mart concept has been adopted, mutated, and remixed by others all over the world. Online learning is today an over 200 billion dollar industry; apps for everything from meditation to mathematics adopt the model of micro-lessons as a key to daily learning. Design weeks– already enormous bustling industry events– became tourist destinations. A crop of websites arose devoted exclusively to free design competitions in collaboration with major brands. These forces can create fertile fields of opportunity for creators just as they can create new gatekeepers and monocrops of content. Intimate micro-communities and highly funded brands both flourish on entirely different tracks. Advertising and centralized power have returned to dominate the major forms of online communication. Our 1999 dream of horizontal creative culture is simultaneously closer and farther away than ever.

So happy birthday to us, and to you, because this is your story too. To those of you who were with us from the very beginning, you know better than anyone it’s been quite a journey together. To our many readers who found us along the way, thank you for meeting us day after day at our newsletter– every USA morning or European afternoon– or whenever you came to the site or scrolled onto our socials. To the teachers who introduce us to your students and to the fans who were inspired to create art or design of your own, to the hundreds of designers and architects we’ve worked with and to the constellation of former staff and interns since scattered back around the world: designboom has your DNA in it.

designboom annual meeting in 2013

DESIGNBOOM JOINS ARCHITONIC AND ARCHDAILY AS DAAILY PLATFORMS

In 2022, designboom, the world’s first online magazine – became part of the NZZ Group and teamed up with Architonic and Archdaily to create DAAily Platforms, the clear global market leader in premium architecture and design. ‘Birgit and Massimo have spent the past 25 years building up designboom with passion and dedication. designboom started out at the same time as Google, before the rise of publishing software and social media and have since become an industry benchmark,’ comments Felix Graf, CEO of the NZZ Media Group. ‘Birgit, Founder and Editor-in-Chief, and Massimo, Founder and CEO, have successfully led the important transition phase from a founder-led start-up to an internationally operating company with professionalized management. They are now stepping down from designboom and we would like to thank them very much for their great commitment. We wish Birgit and Massimo every success in their next steps and look forward to staying connected and continue to support each other in the future,’ adds Martin Zelger, CEO of DAAily platforms.

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.